“The war in Ukraine is the first social media war… it is crowded with fake news and propaganda.”

In a session at Radiodays Europe, Olli Junes, Executive Producer of Radio for the Finnish broadcaster YLE, commented that Vietnam was the first television war, The Gulf War was the first Live TV war, and Ukraine is now the first significant social media war.

“It is a tragedy and the suffereing in Ukraine is beyond words, but we need to cover it.”

Head of Czech Radio’s foreign news desk Philip Nerad and Czech Radio’s Ukraine foreign correspondent Martin Dorazín, who appeared by video link, said:

“Russia has declared an information war on the world, not just in Ukraine, to destabilise societies and push some politicians to the forefront… so we are all at war, not just those who fight on the battle fields of Ukraine, but in all countries.

“So how should journalists behave at this time? We have to solve these questions immediately… editors and listeners do not wait for us to debate and resolve problems about how we should report, we are making decisions about what we cover every day.”

They identified a range of ethical reporting issues in covering the Ukraine War and social media propaganda:

On the questions of objectivity and how to bring verified information to the public, Dorazin said, “our approach is to be on the ground and to bring witnesses.” Nerad confirmed Czech Radio’s commitment to keeping a correspondent in its near neighbour to gather first hand reports, “that is why we have Martin there as a permanent correspondent to Ukraine.”

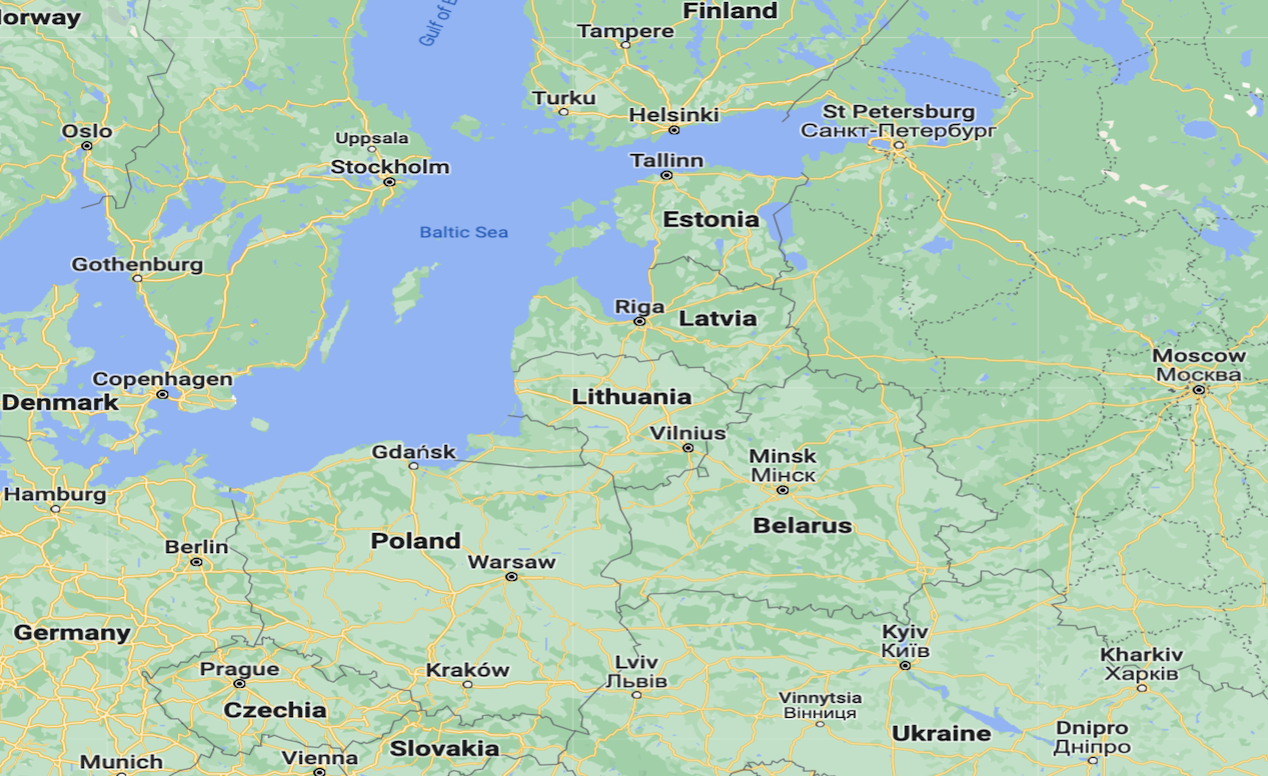

Now that the Czech Republic is no longer part of Czechoslovakia, it does not share a comon border with Ukraine, but its neighbour Slovakia does and many people of the Czech Republic have links with Ukraine. Finland and the Czech Republic well remember the history of communist rule in the region and are watching carefully the current conflict of today.

The challenges for a war correspondent at this time, according to Dorazin, are:

Should the correspondent stay only a passive describer or act? When he was in a building that was attacked, he decided to search for survivors to try to help. “This blurred the boundaries, but it felt like the right thing to do to help an old lady who had survived but was in shock and could not move.”

What can we show and what should not be shown? There are so many horrors, how many dead bodies, how much blood do you show. Some stories have provoked a response from audiences and regulators that the coverage is too graphic. This is an issue in the modern age when radio reporters are no longer limited to filing audio, they must file pictures and text too.

“We also have to be aware of how the reporters and the audience are all coping with the horrors of war.

“It is the first online war. The role of social media is crucial, war reporters now have to be active on social media as a source to counter the unreliable or faked content that is online and on social media.

“It is important to have an online presence, but there are some things to consider, such as delaying before posting, due to security reasons.”

Nerad says he has to look after the wellbeing of his team who may be targeted by the Russian army who use social media locations or known landmarks in pictures. It is not just the reporters who are at risk, it is also their sources, who may be targeted if they are seen in reporters social or online posts.

“War is now online in real time… technology and social media has fundamentally changed war reporting.”

Roman Anin, a Russian reporter and founder of the independent website IStories told his story about going into exile in the Czech Republic so that he could continue to report what is happening in the war without the restrictions of reporting that apply to news publishers inside Russia.

“When the war started I had a choice of two options, stay in Russia or leave and try to tell truth to the Russian audience. It was not an obvious choice for me,” explained Anin. “We were declared an undersirable organisation by the Russian government and can be imprisoned… Any reader who is sharing our content can also be imprisoned.

“Even if you read a post on our site you can be sentenced to jail. Our platforms were blocked.”

Anin told delegates how he and his team moved out of Russian and transformed their news website into a video channel to get around Russia’s content blocking of their main website.

“Telegram and Youtube are the only two channels not blocked so we focused on them… we get 4-5 million views per month on Telegram… we had to become tv journlsists to develop content for Youtube,” he said.

“There are not so many advantages of being a Russian journalist these days,” said Anin. But there was one, “Russians will talk to us,” he explained, recounting the story of one young Russian soldier who was willing to talk because he was disillusioned with the war. “He confirmed a lot of horrible facts that we knew.

“We found his phone and called him back, over time we built a rapport. He called back and he confessed to horrible crimes including the assination of a villager. It was difficult for us… I did not have sympathy for the guy, but on the other hand he was an important witness who was willing to tell us about his and other crimes.

“We knew he would be prosecuted if we published the details he gave us… I talked to the international criminal court who promised to take into consideration his cooperative attitude… he did not take up that opportunity and was recently sentenced to 6 years in prison in Russia, not for killing civilians but for spreading fake news… because Russian soldiers do not kill civilians.

“Without having someone who spoke Russian there on location the stories we broke would to have been possible.”

More than 2 million people viewed that story.

With his Russian perspective he understood the effect of the propaganda, but has seen its effectiveness decreasing the longer the war has gone on. “There were many who supported the war at first, about 80% of the population, but now those who oppose the war has been growing… but there are still a lot of people who hate us because they believe the propaganda and think we are lying and we are spreading Ukrainian propaganda.”

Despite the criticism he received and the threats to his life, he says he is using the power of good journalism for an important cause. “When we think it is difficult, then we look at each other and say, ‘our problems are not as big as those of the people in Ukraine.’”

He says he has “no idea what will happen next,” but does not really want to be a media person working from exile in the long term.

“There is danger for us, even here at this conference, but not as much as the people in Ukraine… I hope what we do is helping bring justice to the Ukraine.”