Read excerpts here and now

You’ve heard of – or more importantly heard Game Changers: Radio: The Podcast.

It’s been a runaway success around the world with radio professionals.

So why write a book? Is it merely a product extension? In which case, why not wait for the movie to come out on Netflix or the X-box release of Game Changers: The Game?

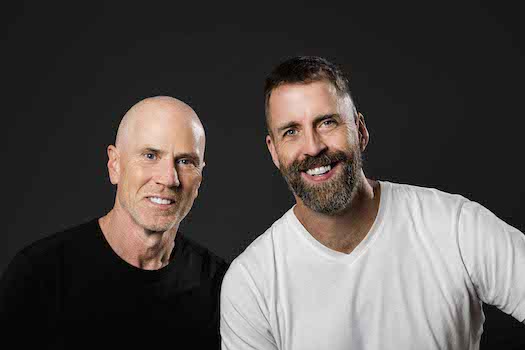

Co-author and producer, Jay Mueller says he and Craig Bruce wrote The Book because “We wanted to pull together the lessons and experiences shared in the interviews in one place. We wanted to connect the dots between the shared experiences of the different people who talked to Craig.”

The book will be available from tomorrow, October 13 through Amazon.com.au and radiogamechangers.com. The authors have been kind enough to provide a few excerpts below which should be enough to whet your appetite.

If you’re going the CRA Radio Alive conference on in Brisbane on October 18, you can see Jay and Craig’s presentation at 3:15pm. This will be the first in a series of events in 2020.

Jay says, “Our primary focus is to provide a resource for people who want to work in radio. If the book helps someone think differently about how they approach their career, then we’ll be happy.

“The main experience with writing the book is that everything took twice as long, sometimes three times as long, as I thought it would take. Our editor, Lorna Hendry, and my partner Astrid Edwards guided us through the process. Without them we would have been lucky to produce a pamphlet.”

Game Changers Radio Excerpts

Chapter Two – The First Job

I didn’t have any bad habits, I didn’t have any good habits

The people featured in this book didn’t arrive behind the mic fully formed. Little by little, incompetence gave way to adequacy. Basic became believable. Novice became professional.

It’s a story that is told repeatedly. Every story involves false starts, tentative beginnings and plenty of mistakes and misdirection.

Chrissie Swan – host of Chrissie, Sam & Browny on Melbourne’s Nova – started her career as an advertising copywriter. She wanted to be Darrin from the 1960s sitcom Bewitched. ‘I just thought that was so cool … I loved the whole idea, but I didn’t think I was cool enough, because advertising was so cool in the 80s and 90s.’

Chrissie has hosted number one Melbourne shows for the Mix Network and Nova, but 20 years ago she was a long way from good ratings.

‘There’s no other industry for a young person like radio,’ she said. ‘It is full of fun people, or it’s full of crazy people, which is just as important … and it’s got lots of assholes, which is really important that you get to deal with … and you’ve got the chance to go and work at 7HO (Hobart, Tasmania) or you know, funny little stations where you meet other amazing people and you’ve got to live on 200 bucks a week and you’ve got a share house with seven people. There’s no industry like it.’

The willingness to do whatever it takes is a consistent theme among every first job story. In the early days of The Hamish & Andy Show, Andy Lee discovered that his willingness to do whatever it takes involved copious notes and daily air checks.

‘I was a prolific note taker,’ he said. ‘I loved the air checks. I think most people in radio would spew at the thought of them. I loved them. Because I just wanted to know how they think – as in the bosses or other people – so we could improve. I’d make really clear notes about what I wanted to achieve.’

From his notes, Andy would give himself performance goals, usually two or three points to focus on during the next shift.

‘I’d sit there [before the next show] and I’d look at that air check and those clear things like “Don’t do again”. I wasn’t going to make the same mistake twice. We’d enter that show and I’d have them clearly on my mind. If we had a lot of notes, I’d go, “OK, now which ones are the ones I want to do this week?”’

The air checks, the notes and the performance goals worked together. They were his baby steps, his deliberate practice. ‘It becomes muscle memory. Quickly. Particularly when you’re learning the habits.’

Learning the habits. It’s another of the first-job themes. Your first job will provide an abundance of opportunities. Quite possibly the greatest one is the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from those mistakes.

‘I didn’t have any habits at that point,’ said Andy. ‘I didn’t have any bad habits. I didn’t have any good habits. I was just trying to establish habits. I was like, “Well, let’s make sure it’s these habits”.’

Chapter Three – The partnerships

Forget viral, focus on primal

One of the things I noticed when I started working with Kyle Sandilands and Jackie O in 2004 was how tight they were off air. They were totally invested. They worked hard on developing their relationship, and consequently their chemistry, away from the studio. I’m not sure whether it was a strategy or if it was just a case of them genuinely enjoying each other’s company. Probably the latter.

The ease of conversation and sense of predictability they have for each other on the air has been supported by years of socialising away from work. They don’t do it as much anymore, but in the early stages of the partnership, when it mattered most, it was all about how strong and united they could be on all aspects of their brand.

The first piece of advice I offer every new show is for the co-hosts to wholeheartedly invest in their relationship. You can’t have success in isolation on breakfast radio, particularly when you’re starting out, and there’s very little chance of a genuine connection without a commitment to understanding each other.

Understanding doesn’t have to include ‘liking’. Gene ‘Bean’ Baxter appeared in Episode 100 of Game Changers: Radio. He and his on-air partner, Kevin Ryder, have hosted the breakfast show on KROQ in Los Angeles for 30 years.

‘Our situation is … different. We are not close personal friends. We don’t spend that much time together … we save our interactions for on the air. We are tremendously close business partners, but we’ve never been really, really close friends off the air,’ Bean said.

‘You go to work and you know the other person is going to make you laugh … We’ve both respected the other person’s opinion, we’re both trying to make the show as good as we can, and we trust each other,’ Bean said.

In very simple terms, the teams that build longevity based on mutual trust and respect, almost always win the radio ratings game.

This goes to the heart of our jobs – we’re in the business of creating new habits or changing old ones.

Which is much harder than it sounds.

Chapter Four – Write it down

You can replace words with attitude

While Tony Martin and Mick Molloy read their own jokes, Andrew Denton wrote jokes for radio original, Doug Mulray. Doug is considered one of Sydney’s most successful FM presenters, and his show captured the essence of Sydney in a way that hasn’t been replicated.

‘I used to sit there with this stack of little yellow notepad pieces of paper, and if I thought of a line, or a joke, or whatever, I’d just write it and give it to Doug,’ Andrew said. ‘Sometimes there would just be a line, but sometimes they were a couple of minutes long, and sometimes … he’d grab something … read the first two lines and then launch into it. And there were a few times where Doug would be reading something I had written, and I was still finishing while he was reading it.’

That story is an extraordinary example of trust between performers. The trust to start reading something on air without knowing how it ends. Andrew, of course, went on to write and research his own interviews and is now one of the most respected performers in Australia.

Writing for radio helps you identify where things end. Lee Simon remembered the one rule he was told to follow early in his career.

‘Work out how you’re going to start and how you’re going to finish. So, if you get lost in the middle, you know what your finish is going to be … the basics are still the basics. It’s how you use the basics,’ Lee said.

Scott Shannon shared stories from his time as a programmer when he encouraged – often demanded – his announcers write down their breaks. Every word. With the sole purpose of charting a path from the break’s beginning through its middle, all the way to its natural, and planned end.

‘People would grumble about it,’ Scott said. ‘‘Oh, come on, I’m a DJ. I just hold the mic and talk.” Every so often, I’d pop in and say, “Let me see what you wrote for that last break”. And they’d say, “Uh, I didn’t do it that time”. “Well, it sounded like it,” I’d say. “Keep doin’ that and you’ll be babblin’ somewhere else.’’’

For Scott Shannon, the writing isn’t just about knowing what to say, it’s about realising you don’t have to say that much.

‘When you write it and you see how many words you can take out that aren’t necessary, it’s very important. You can actually eliminate words. You can replace words with attitude,’ he said.

Chapter Six –

No hugging, no learning

In a world full of content in the palm of the listener’s hands – the previously mentioned attention economy – the skill of content curation has never been more important.

Great shows not only curate on behalf of their listeners’ expectations, they curate based on their natural strengths as performers.

In the early stages of the Kyle & Jackie O show on 2Day FM, my traditional programming inclination was to push them towards the dominant news stories of the 24-hour cycle. This was a typical, formulaic approach to finding content that works for most breakfast shows.

Not Kyle and Jackie.

The result was that, while every other breakfast show in Sydney was talking about the same things, Kyle and Jackie were in their own patch, making their own news.

Very few shows can pull this off, but the ones that can, succeed.

If you’re on a new show or you’re developing some basic music announcing skills, here’s how you can replicate the principles of zigging when others zag.

The one thing these shows had in common was a vision.

A vision that was aligned to the natural strengths of the show’s performers.

A vision that ran counter to the radio norms of the time.

A vision that was narrow and clearly understood by everyone working on the show.

The narrower the brief, the better the result.

Lorne Michaels, the legendary creator and producer of Saturday Night Live said this on Alec Baldwin’s Here’s the Thing podcast: ‘To me there’s no creativity without boundaries. If you’re gonna write a sonnet, it’s 14 lines, so it’s solving the problem within the container.’

This idea of a narrow brief is platform agnostic.

Larry David – creator, along with Jerry Seinfeld, of Seinfeld – had a five-word content filter for the show: ‘No hugging and no learning.’

Think about it.

Did you ever see a happy ending on Seinfeld? Did they ever have a ‘moral to the story’ at the 22-minute mark of the show? Can you remember a single romantic moment that didn’t get real weird real fast?

‘No hugging and no learning’ was both the moral compass and key content filter for the show.

There are many reasons why Seinfeld was successful, but the fact that it ran counter to every other sitcom in prime time was one of its great strengths.

If you’re new to radio, you don’t need a fully formed vision statement or a vision document, but you do need to start thinking about the kind of radio presenter you want to become and the kind of radio show you’d like to create.

Take inspiration from your favourite shows (who doesn’t want to be the next Hamish and Andy?), but study their technique, don’t mimic their style.

Chapter Seven – The Deals

Everyone loses their aura when they’re sitting on a tiny chair

‘Brad had been very diligent,’ Andrew Denton said about March’s efforts to lure him back to radio. ‘He approached me many times … Brad knew radio and he knew what he was after and so I trusted that conversation … He said, “Come and do radio”. And I thought, “I really don’t want to do television, so I will try this … I loved working with Doug [Mulray], I’ll see if I can do it … under my own banner.”’

Once March convinced Denton to consider returning to radio, Denton began the negotiation for his show.

‘To give you an example of how I like to operate, one of the things I do when I have negotiations with people is, I will always insert some tricky humour in there to see how the people I’m negotiating with are going to respond, because if they don’t respond well, that tells me something about them.

‘So, we had a secret meeting in the hotel room, it was Brad and it was Cathy O’Connor and could have been Dobbo (Guy Dobson) … and I got to the room first. And it was one of those little conference rooms where there were little notepads and pencils. So, before everyone got it, I wrote little notes on the notepads, saying things like, “Pay this man the most money possible”, [and] “This man’s extraordinary”. Everyone gets into the meeting and nobody’s looking at the notepads. We’re all just chatting away and I can see, as the meeting’s going on, people glancing down at the notepads and just looking a bit like, “What?”’

Andrew Denton is not the only person with a humorous approach to negotiations. Mick Molloy once conducted a negotiation in the office he and Tony Martin shared on Austereo’s Melbourne rooftop.

‘I remember once Brad March was coming down with Peter Harvey [Austereo executive chairman],’ Mick Molloy said about an incident during the Martin/Molloy days at Austereo. ‘We said, “They’re coming around, they want a meeting” … so we went out and bought the smallest chairs we could find … they were like from a kids’ shop. [We] sat them around a table like this one [a low coffee table where we recorded the interview], and we said, “Guys, come on in, please sit down”. We were on tiny chairs too. We’re just laughing at the two most powerful men in radio sitting on the tiniest chairs. Everyone loses their gravitas; everyone loses their aura when they’re sitting on a tiny chair.’

Chapter Nine – The executives

Long hair and swagger

‘I would think I was doing completely brilliantly and then we always have to go in and have a stupid air check afterwards, and we’d be given a mark out of 10,’ Wendy Harmer said about her early days working with Brad March at Austereo. ‘I would think I’d done a fabulous show and I’ll be getting a six! I’m kind of, “You can’t be serious”.

‘One of the biggest fights we had to have spilled out into the foyer with me yelling at Brad across a crowded sort of marketing jock’s room. “And guess what else? I’m older than you. I’m smarter than you and I earn more money than you!” Slam.

‘So, the next time I went into Brad’s office, he had pinned on the wall “10 Tips for Dealing with Difficult People”. Brad was really an extraordinary person to work for because he’s just relentless about getting it right. He just does not give up. He works so hard.’

Jamie Dunn worked with Brad and Wendy. ‘Brad created a garden, a radio garden that would grow an idea from anywhere. And the staff knew that. And everyone was ready for ideas. And that’s what Brad created. And he employed from within. If he saw someone that had a talent, he had no fear, and I loved it.’

A programmer’s influence can be both subtle and obvious. There is an invisible quality to the work that a Brad March or Brian Ford perform. There is also a vision that must permeate every aspect of a station. This is the obvious influence that extends beyond the individual shows.

‘Radio can change on a dime,’ said Jeff Allis. ‘You can put a new program director, a good one, into a radio station, and that program director – if they’ve got a strong enough personality – can put their personality on the station and change the sound, and make it sound like a great, successful radio station very quickly … tracking would go through the roof.’

Programmers do several things that contribute to a station’s culture: they can create an environment for ideas to flourish and they can combine their attitudes with the station’s sound. A station’s culture is often overlooked. There are successful cultures that don’t translate to successful shows. There are toxic cultures with exceptional shows. When a successful culture combines with successful shows, the results are dramatic and long-lasting.