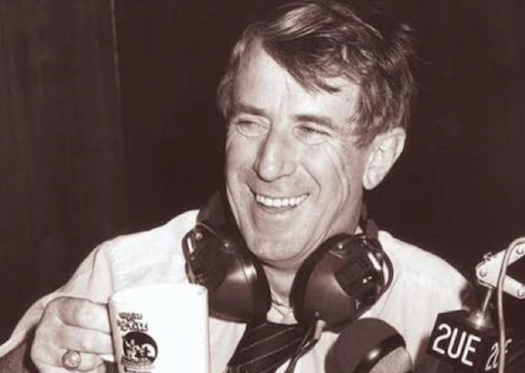

Gary O’Callaghan passed away several weeks ago, with a funeral held at Port Macquarie.

Loyal audience members and colleagues of the 2UE breakfast star will be able to pay tribute to the professional man who topped the ratings for more than three decades at a memorial service at Sydney’s St Mary’s Cathedral at 11am Monday.

No doubt he will be remembered as a great contributor to Sydney’s society and culture over half a century, yet it is his six children who hold the fondest, most personal and wonderful memories.

radioinfo is honoured to publish his eulogy, as contributed to by all six children, with Lucy doing the final edit for reading by Ann, Kieran and John..

Our Dad’s mum, Eileen, was sitting on the Bondi Tram in Sydney on her way home from convent school at age 14, when she glimpsed out the window and discovered her father was gone forever.

“Actor dies on stage” read the Sydney Morning Herald banner she could see on a poster outside a newsagent.

Her dad, Walter Dalgleish, a celebrated theatre actor, had died during his star turn in the final act of a play in Fremantle, Western Australia.

The audience thought his death was all part of the performance and didn’t realise something was amiss until the curtain went down. It has been the O’Callaghan family motto for generations: the show must go on.

Little Eileen, whose mother was a theatre wardrobe mistress, would blossom into an admired performer herself: a glamorous soubrette, whose lively singing and dancing entertained thousands.

So it was no surprise when our grandmother fell in love with and married drummer John Patrick O’Callaghan – himself a member of a generations-old theatrical family – while they both were on tour in New Zealand.

Then along came daughter Maureen and, six years later, baby Gary Bernard O’Callaghan made his debut at a St Kilda Hospital in Melbourne on October 11, 1933. Pa, as we grandchildren called dad’s father, would make his mark in the industry as an executive for Hoyts Theatres during the golden years of Hollywood.

Dad and Aunty Maureen, along with our grandmother, and Eileen’s adored and revered mother Nanny, would follow the family breadwinner as he was promoted back and forth between Sydney and Melbourne for much of their childhoods. It didn’t matter which city they called home, though: the O’Callaghan parlour always was filled with actors, singers, comedians, dancers and writers. And always jokes and laughter.

Entertainment simply was in Dad’s DNA.

At age 17, Dad landed a job as the office boy at the then Catholic-owned radio station 2SM, and his destiny was sealed. It was at the station in 1954 when our news-driven, ambitious Dad’s life changed forever, and he discovered there was something in the world far more important than ambulance chasing.

Dad had just finished the breakfast show when he picked up the phone and a lilting voice answered: “waiting”. Dad put down the phone and hurried to the office area where, he said later, he found a young, smiling brunette, who wore shoulder length hair and a big smile, behind the switchboard.

Dorothy McManus turned dad’s head all right. It didn’t shift away one degree from those beautiful brown eyes during the more than 60 years that followed.

In fact, just weeks ago, when Dad was so terribly sick in Port Macquarie Base Hospital’s intensive care unit, where had only just been taken off life support, he convinced a nurse to phone their Sancrox home one night.

He was barely able to talk, and clearly in a great deal of pain, but he had to speak to Mum to make sure she was well, whether she needed anything, and to tell her he loved her.

Mum and Dad’s enviable love and devotion produced three boys and three girls, in that order, in the 13 years that followed their 1955 wedding.

It made us the luckiest children on earth.

Dad taught us about love, loyalty, dedication, personal sacrifice and a fine work ethic.

But he didn’t ever let his job or his selfless, unpaid work for dozens of charity organisations and the police fire and ambulance interfere with his favourite role as husband and father.

He would get up at 3.30 each weekday morning, six days a week some years, and often would not climb back into bed until midnight or later the following day. But he always tried desperately to pick us up in the car each school day at 3.20pm, so we didn’t have to catch the bus home.

Yes, he was power-napping in the driver’s seat when we opened the car door. But, within seconds, Dad was at full throttle wanting to know about our days and sharing his own often amazing adventures as he drove us home to Mum. He’d nod off at family picnics or out fishing or visits to Kur-ring-gai National Park and serenade us with a snore for 20 minutes before switching back to Dad in top gear.

We all have hilarious memories of nightly family dinners, where Dad stirred the pot in heated debates on wide-ranging subjects from politics and religion to show biz and the introduction of supermarkets into Australia.

It developed in our young minds the ability to to think about, question and challenge the world beyond our home and classrooms. He listened to all of us equally, whether we were five years old or 17. But he did particularly enjoy baiting the older boys and watch them fall into his argumentative trap, hook, line and sinker.

None of us can forget the 1975 Whitlam Dismissal debate. It almost caused an O’Callaghan constitutional crisis. Sometimes the meal would go on for hours and the youngest girls were almost snoring in their dinner plates.

But, as we were not allowed to leave the table until Dad had finished his meal and we could seek permission to go to bed, our father would leave one measly mouthful of potato on his plate, with his knife and fork apart. He decided when the show was over.

Our home was always filled with laughter. Dad found jokes made at his expense particularly funny. We laughed until tears rolled down our faces, our bellies hurt, and one of us developed the hiccups.

Music filled the house in Holmes St, Turramurra, where the family lived for more than 30 years, too.

Dad would enter the kitchen and swing his beloved Dorothy Jean Angela in a two-step to his favourite song, Home on the Range.

He taught the girls to waltz by putting their tiny toes on his shoes and twirling in the lounge room to Strauss’s The Blue Danube.

Then there were the unforgettable stories he created when we were about to go to sleep at night. Dad’s imaginative word pictures took us on drama-filled family journeys around the world by yacht; we drove into the Australian desert and became lost; some of us even got to join the circus.

He embarrassed us, too. Deliberately of course. The picture of Dad walking along the beach in long white socks and white covered shoes – because he didn’t like sand between his toes – still makes us shudder.

Most importantly, dad taught us to follow our life’s dreams, and that when one of those dreams didn’t come true, how to pick ourselves up and strive for another. In fact, Mum always called dad her Walter Mitty, the fictional daydreamer. And he certainly was.

Dad wanted to be a fireman, a barrister, a police officer, a train driver, an airline captain, an ocean liner captain, a music conductor, a jockey. In fact, he first decided he wanted to be a jockey when he was sitting on that same Bondi tram line as his mother had been decades earlier.

Dad was heading home from Waverley College aged about 10, and looked out the window as a huge funeral procession passed. It was for a famous rider who had died in a fall at Randwick the previous week.

That’s when I decided to be a jockey because that’s how I want to go out of this world, he would often tell us. And thanks to his wonderful friends in the NSW Police Force, that is how Dad is taking his final bow today.

It’s a fitting tribute to a true gentleman and gentle man who entertained us every day of his life.

I was at Dad’s bedside when he took his final breath.

He briefly opened his big blue eyes long enough for me to tell him, don’t worry dad. The show goes on.